It may sound obvious that detecting cancer is a good thing. The ideal screening test for cancer will identify people without symptoms, yet find aggressive cancers before they have metastasized (spread). Under these circumstances, a test will not only reduce the risk of death from the cancer being screened for, but it will lead to a longer life overall. But not all screening tests are equally effective, and not all cancers necessarily require treatment if they are detected by screening. When you combine an imprecise test with a cancer that can be slow-growing and may not even cause harm, there is the significant risk of overdiagnosis and overtreatment. That’s the current controversy in the screening and treatment of prostate cancer, and the value of the prostate specific antigen (PSA) blood test. Prostate cancer is a major cancer killer in men. Yet far more men die with prostate cancer than of prostate cancer, as prostate cancer can be slow-growing, non-invasive, and never cause any harm. Now there is new data to inform decision-making about whether men who are free of symptoms and over the age of 50 should have their PSA tested.

The PSA controversy

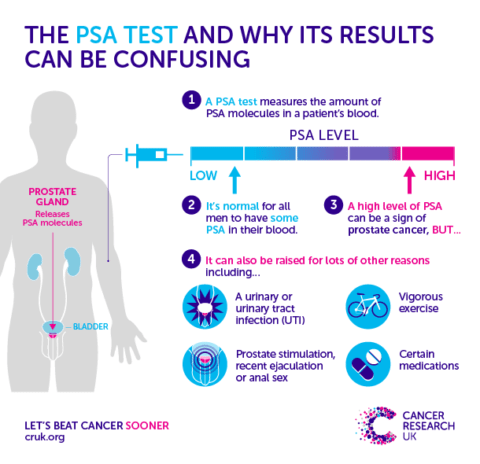

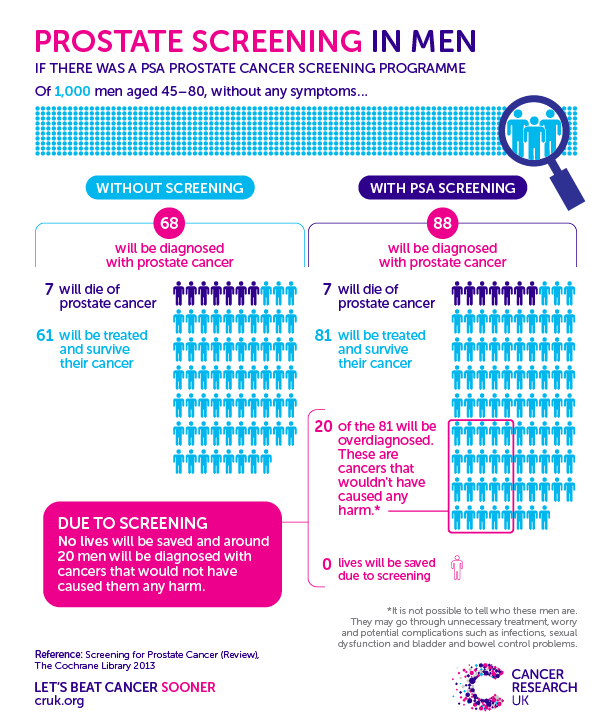

PSA testing is controversial. The prostate specific antigen is a protein produced by the prostate. It became accepted as a screening test in the 1990s, before there was good evidence that it effectively reduced mortality from prostate cancer, or mortality overall. This blood test, along with a prostate digital examination, is one of the ways that prostate cancer can be detected, as PSA can be elevated years before prostate cancer causes symptoms. However, the results of PSA testing are imprecise, and high levels do not necessarily signal that one has cancer, as this infographic explains:

Image courtesy of Cancer Research UK

Benign prostatic hypertrophy and prostatitis are other conditions that can raise PSA in the absence of cancer. The positive predictive value for a PSA level that exceeds 4 (the usual threshold) is estimated at about 30%, meaning that less than one in three with a “high” PSA will actually have cancer revealed after a biopsy. Harriet Hall described back in 2012 that when it comes to prostate cancer, large numbers of men are being harmed by over-diagnosis and subsequent over-treatment, with surgery that can leave men incontinent and impotent, and no evidence that this approach offers any advantage over “watchful waiting” for most men.

A very brief review of the PSA screening literature

There are two papers commonly cited when it comes to PSA screening. The first is from Andriole and colleagues, and is titled “Prostate cancer screening in the randomized Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial: mortality results after 13 years of follow-up,” more commonly called the PLCO trial. The PLCO trial randomized men to annual PSA testing and digital rectal exam (DRE), or to “usual care” which sometimes included prostate screening and sometimes did not. The PLCO trial found, not surprisingly, an increase in prostate cancer detected in the treatment arm. However, there were low mortality rates in both groups and there was no significant difference in deaths due to prostate cancer, even after 15 years of follow-up. Notably, the trial has been criticized for “contamination”, in that most men in the control arm had at least one PSA test over the course of the study. So it’s argued that PLCO is actually an evaluation of more versus less PSA testing, rather than an evaluation of PSA testing itself.

The other major study is from Schröder and colleagues, and it’s entitled “Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up” which we will refer to as the ERSPC trial. This was a multi-country European trial that evaluated PSA testing and it found that PSA testing did result in an absolute risk reduction of 0.11 per 1,000 person-years, or 1 prostate cancer death averted per 781 men invited for screening. This is about a 20% relative risk reduction. Another way to state the results is that 48 additional patients need to be diagnosed with prostate cancer to prevent one prostate cancer death.

The PLCO study and the ERSPC study had different findings, except for the most important outcome. While ERSPC was the only trial that found a prostate cancer survival benefit, neither study found any overall survival benefit. The best we could conclude from these two trials was that PSA testing may reduce death from prostate cancer.

The new study

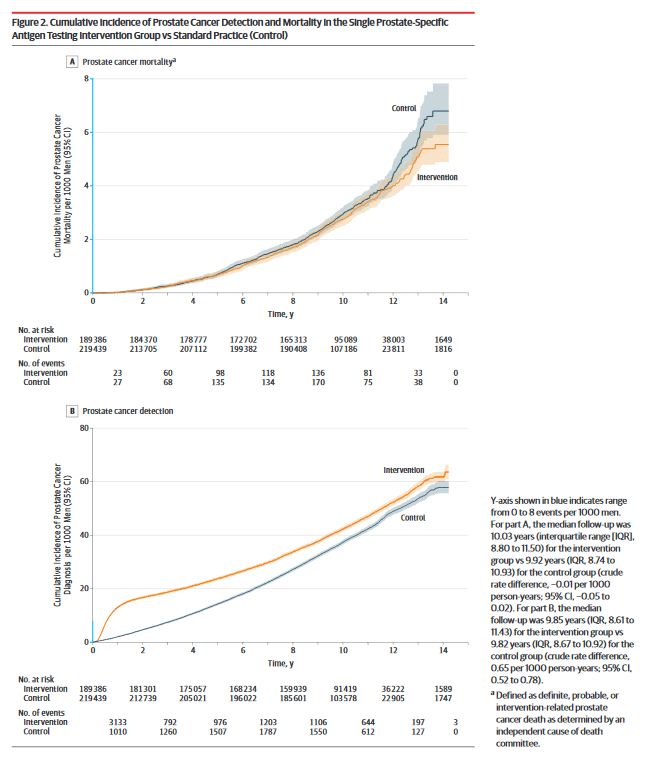

This new study addresses one of the criticisms of the PLCO trial. If the PLCO trial was “contaminated” by testing in the control arm, then a better study would evaluate PSA versus no testing at all. That’s exactly what this study did. It’s from Martin and colleagues and is called “Effect of a Low-Intensity PSA-Based Screening Intervention on Prostate Cancer Mortality” (the CAP trial). It included over 400,000 British men aged 50-69. Men were randomized into an RN appointment, where they were offered information on a PSA test, and if they chose, the test. The other group didn’t invite men for testing. After a 10 year period, the study found that there were more prostate cancers detected from this one-time testing. However, this group was no less likely to die from prostate cancer. Here’s the key finding – no difference in mortality between the two groups:

The one-off PSA test detects cancers, but doesn’t save lives from prostate cancer. Vinay Prasad pointed out on Twitter out that prostate cancer mortality was small in the study, compared to overall (all-cause) mortality:

This infographic from Cancer Research UK summarizes the implications of PSA screening, and draws on data from the Cochrane Review:

Image courtesy of Cancer Research UK

To PSA screen or not?

Prostate cancer is a major killer of men and it is admittedly frustrating that the PSA test is largely ineffective as a screening tool. Given there is still no effective way to identify the prostate cancers that really need to be treated, the PSA as a screening tool is leading to overdiagnosis and overtreatment, with the resulting harms. What this evidence means for men is that if you lack any symptoms of prostate cancer, PSA testing has significant risks. It is important to understand the overall risks and the small (if any) benefits. Whether you have prostate cancer detected or not, there is an equal chance of you being alive in 10 years. For health professionals, PSA testing mandates a detailed discussion with patients on the risks of screening. Screening and dialogue tools may be helpful in translating the findings of the accumulated research, ideally leading to shared decision-making. While it’s important that there is continued research into better screening and treatment tools for prostate cancer, we must also use the evidence we already have on PSA screening to reduce practices that harm men and offer no clear benefits.